Product test

Hands-on testing the Sony Alpha 9 III: quick as a flash thanks to global shutter

by Samuel Buchmann

Sony has managed a technical breakthrough with its release of a camera with a global shutter. Get answers to six of the most pressing questions about this groundbreaking technology right here.

The Sony Alpha 9 III is causing a huge stir in the world of photography. Why? Because it’s the first full-frame CMOS camera to have a global shutter. So what does that entail? What does it do and what does it mean for the future? Here are the answers to the six most pressing questions.

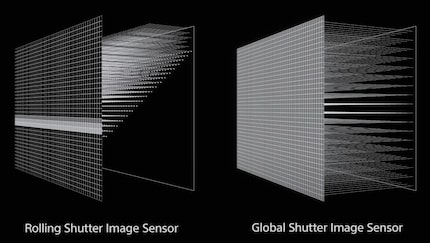

It’s a process that reads all pixels of the camera sensor simultaneously. The term «shutter» is actually a bit of an outdated term, but it’s important to understand it.

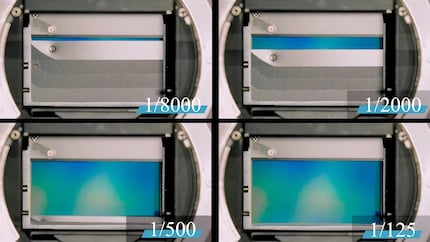

Classic cameras have a mechanical focal plane shutter that opens and allows light to fall on an analogue film or digital sensor. It then closes again after a specified time. How? With the help of two shutter curtains, with the second one following the first. For fast shutter speeds, the focal plane shutter never fully exposes the entire sensor. What happens is that the second shutter curtain begins to cover the sensor again before that happens.

For SLR cameras with an optical viewfinder, the mirror must first be folded out of the way for this process. More recent camera models no longer need to do this, as they have an electronic viewfinder that takes the image directly from the sensor. This has paved the way for a different type of «shutter»: the electronic kind.

With an electronic shutter, the sensor’s permanently exposed. When you press the shutter release, the camera reads out the image at that very moment and saves it. Previous CMOS sensors do this line by line. The camera reads the top row of pixels first and works its way down to the bottom. This takes a certain amount of time, which varies depending on the sensor. Take the Sony Alpha 7R V, for example. It has a back-illuminated sensor and 61 megapixels and takes around 1/30 of a second. The Nikon Z 8, with its stacked sensor and 45 megapixels, needs just 1/270 of a second.

The new Sony Alpha 9 III is the first to do things completely different. The camera fully activates the sensor immediately and reads all pixels simultaneously – a genuine technological breakthrough.

The global shutter eliminates several problems that other shutter systems struggle with. It also opens up new possibilities:

The advantages of the global shutter are particularly noticeable in three cases:

Apart from that, the global shutter will make a mechanical shutter superfluous in the future. This eliminates a complex component. Cameras could be designed to be more compact – and more affordable. However, the price reduction’s only likely to happen in the long term. Like any new technology, the global shutter will remain expensive for some years to come.

Despite its advantages, the Sony Alpha 9 III is the only camera of its kind that’s currently only of interest to a very small target group. If you don’t take pictures of fast sports, you’ve probably never had a problem with distorted images. Not even animal photography benefits greatly from the global shutter. The rolling shutter effect regularly occurs when filming with regular sensors, but these are already well under control with new cameras. And if you tend to use your flash in the studio and not outdoors, you’ll hardly ever need fast shutter speeds anyway.

Yes, but at under 1/1000 of a second you won’t get much out of it. Sony advertises synchronisation times of up to 1/80,000 second for the Alpha 9 III. Although this is possible, it’s also pointless. Why? Because at very fast shutter speeds, the flash unit becomes a bottleneck. A flash tube needs a certain amount of time to emit its light. This is referred to as burn-off time. If the global shutter exposes the sensor for less long than this burn-off time, it no longer picks up part of the flash light. As with continuous light.

Here’s a little deep dive if you want to know exactly how long typical burn-off times are and what the specifications mean. If you don’t care, just scroll down to the next point.

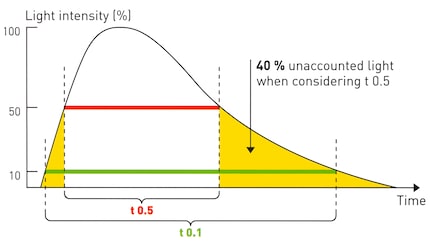

The light intensity of a flash tube isn’t linear, but a curve that rises quickly and falls slowly. The stronger you set the flash to, the longer the burn-off time. It’s specified as T.5 or T.1. T.5 indicates the time that the flash shines at more than 50 per cent intensity. T.1 indicates the time it shines for at more than 10 per cent intensity.

T.1 is the relevant specification to estimate the shutter speed at which a global shutter no longer captures all the light. T.5 is misleading, because the flash has usually only emitted 60 per cent of its light at this point. Unfortunately, many manufacturers only specify T.5 because it looks better. Now that you’re armed with this knowledge, here are a few examples:

As you can see, the T.1 burn-off time of most flashes at full power is a good 1/300 of a second. Even if you accept a light loss of around 40 per cent, you’ll hardly achieve more than 1/1000 of a second. Faster shutter speeds only make sense if you don’t set the flash to full power – but then you have no additional advantage in the fight against the sun.

A sensor with a global shutter requires an extremely large number of circuits in a very small space. After all, the signals from all pixels must be transmitted simultaneously. This is only possible in a stacked sensor, as the photodiodes and circuits aren’t arranged on the same level, but one behind the other. A conventional sensor probably wouldn’t have enough space for this.

Not to mention that it’s an expensive construction. This was already the case with regular stacked sensors. With an additional global shutter system, they’re even more difficult to manufacture. That explains why it took Sony so long to develop it. What’s more, the complexity of it could have a negative effect on image quality. Namely:

Sony claims the global shutter in the Alpha 9 III doesn’t lead to poorer image quality. But this will only be verifiable with the final cameras and RAW images. In the first hands-on test with a pre-production model, I didn’t notice anything negative in terms of image noise or dynamic range.

The resolution of the Sony Alpha 9 III is a solid 24 megapixels – which is probably the limit of current production technology. More pixels would mean even more circuits.

The next camera that would be suitable is the Canon EOS R1. It’s also a sports photography flagship. According to rumours, it will be launched in early 2024. Apart from Sony, Canon is the only manufacturer that builds its own sensors.

However, it’s impossible to guess how quickly Sony will share its technology with other brands. The group supplies sensors to almost the entire industry: Nikon, Fujifilm, Hasselblad, Olympus, Apple. Sooner or later, the global shutter is likely to make its way into other high-end cameras. However, it’ll probably take longer before it’ll be featured in mid-range cameras. Even regular stacked sensors are still reserved for the flagships. The only exceptions so far are the OM System OM-1 and the Fujifilm X-H2S. Both in smaller formats.

Would a global shutter in smartphones also make sense? In theory, yes. After all, they also read their sensors line by line. But the sensors are tiny – no larger than 1 inch (which in reality means only a 0.63-inch diagonal). -Therefore, the readout speed is very high. The iPhone 15 Pro, for example, manages 1/200 of a second.

In practice, the rolling shutter effect is therefore only a problem in extreme situations. Similar to the stacked sensors of the Sony Alpha 1 (1/240 s) or the Nikon Z 8 (1/270 s). Unlike larger cameras, a smartphone will hardly ever be in a situation where distortion becomes visible. Usually, it wont’ have to synchronise with flashes either.

Header image: Samuel Buchmann

My fingerprint often changes so drastically that my MacBook doesn't recognise it anymore. The reason? If I'm not clinging to a monitor or camera, I'm probably clinging to a rockface by the tips of my fingers.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all