Copy protection: the music industry’s eternal battle

From audio cassettes to DAT and burned CDs to digital downloads – the music industry has historically fought any technology allowing listeners to record or copy music. Sometimes with questionable methods. The advent of streaming has changed a lot – but not everything.

Leading into the seventies, the music industry is in good order. Music is pressed onto vinyl records; other audio recording mediums are effectively immaterial. Vinyl records are cheap for record companies to produce, but impossible for private individuals to copy.

This changes with the advent of magnetic tape, which makes its way into the home in the form of reel-to-reel tapes as well as audio and video cassettes. Magnetic tape makes not only playback possible, but also recording. Thus begins a long battle between those who buy – or don’t buy – music and those who sell it.

Audio cassettes: the moral cudgel

At first, the situation isn’t overly dramatic. Tape recorders that offer high sound quality are expensive and mainly reserved for the studio. Although the compact cassette was invented as early as in 1963, it would deliver poor sound quality for a long time to come. So, cassette recorders are mainly viewed as dictation machines.

But in the seventies, sound quality improves for a number of reasons, including the introduction of lower-noise tape material as well as Dolby noise reduction. The main driver of quality, however, is competition among Japanese hi-fi companies. By now, the tape recorder is definitely seen as more than a dictation machine. And thanks to the popularisation of the Walkman in the eighties, the cassette becomes the first portable recording medium.

BPI, the UK’s recorded music industry’s trade association, feels that it’s time to act. In 1980, it launches a campaign with the slogan «Home Taping Is Killing Music». The logo features a cassette shaped like a skull with the aim of appealing to people’s conscience.

Source: Shutterstock

If you record your own vinyl onto cassettes so you can listen to music on the go or keep your records in shape, you are – according to the BPI – killing music. Needless to say, nobody buys this nonsense. While the campaign is well known, it doesn’t achieve the desired effect. What remains are its numerous parodies, like «Home Cooking Is Killing Restaurants». Or – my personal favourite – «Home Taping Is Skill in Music», a reference to the art of making a good mixtape.

With audio cassettes, it’s technically not possible to prevent copying. With video cassettes, on the other hand, it is possible: Macrovision’s copy protection works by sending out a noise signal that’s imperceptible in the original, but renders any recording unusable. You can see it in action in this video by Technology Connections.

Digital Audio Tape (DAT)

In recording studios, the digitisation of music has its roots as early as in the late seventies. By the mid-eighties, it has also found its way into the living room. To start off, this is thanks to the CD player, which, being a playback-only device, is very much to the music industry’s taste. However, efforts are already underway to digitise the analogue cassette, which was the standard until now. This would give private individuals the power to create their own digital recordings in excellent quality. In 1986, Sony develops a recorder for DAT (Digital Audio Tape) cassettes – and it’s ready for mass production.

Source: Shutterstock

However, the market launch is delayed – and not because the technology isn’t mature. On the contrary: DAT is too good. The high quality of the recordings puts the music industry in a tizzy. RIAA, the USA’s music industry association, wants to prevent the introduction of this technology, which it has deemed dangerous, at all costs – and declares war on Japan.

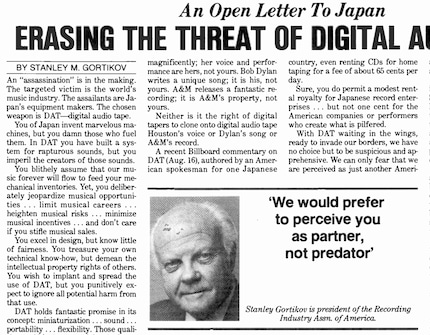

War? Seems like a drastic choice of words. But it’s just as drastic as the choice of words by Stanley Gortikov, president of the RIAA. He writes several open letters to Japan. In these letters, he indeed addresses the Japanese people («you of Japan»), and not Sony, the company that developed DAT. The first of these letters reads as if the Japanese were planning to attack Pearl Harbor again – Gortikov opens with «an ‘assassination’ is in the making» and «the targeted victim is the world’s music industry». He calls Japan’s equipment makers «the assailants», and DAT their «chosen weapon». The article clearly expresses the grievance that Japan has seized technological supremacy – and this despite the alleged fact that really good music still overwhelmingly comes from America. Gortikov writes, «You of Japan invent marvelous machines, but you damn those who fuel them.» He argues that Japan demonstrates its contempt for the copyright owners of foreign recordings, for example, by allowing «2,400 record rental shops to operate … even renting CDs for home taping for a fee of about 65 cents per day». He further alleges that «not one cent» goes to the «American companies or performers who create what is pilfered.» Now, he says, DAT is «ready to invade our borders»; and so, he claims the Americans have no choice but to assume they’re «just another American industry to be trampled on or exploited by Japan.»

Source: Billboard, 06.09.1986

After Gortikov effectively «cancels» the Japanese, he advises them to seek out a dialogue with key players in the American music industry. So what’s the RIAA’s demand? Well, it wants DAT recorders to be required to include a copy-code chip by law which would block the duplication of copyrighted recordings. By this point in time, CBS had already developed the «CopyCode Scanner System» for this very purpose. However, it doesn’t quite work as it should. It produces audible filter effects and doesn’t reliably prevent copying.

DAT manufacturers come up with their own copy protection scheme as a counterproposal, namely the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS). It allows the private copying of purchased music, and only prevents copies of copies from being made. The SCMS is waved through by U.S. lawmakers. But that’s not enough for the American music industry. In 1990, a class action lawsuit against Sony is filed, and labels refuse to release their music on DAT. An ironic aside: through its acquisition of CBS, Sony itself has since become part of the American music industry.

All this leads to DAT being dead before it was ever really born – with one exception: the music industry is more than happy to use DAT often for its own purposes. In studios, DAT is used for final mixes.

MiniDisc

It’s likely that DAT’s flop doesn’t solely boil down to the music industry’s resistance. The technology is complex, expensive, and overshoots the mark for many individuals who don’t need studio-quality sound. For these consumers, Sony develops the MiniDisc, which it launches in 1992. MiniDisc uses a highly compressed format whose sound quality is audibly inferior to that of the CD, at least initially.

The music industry is much more laid back about the MiniDisc than DAT. This may, in part, have to do with the inferior sound quality – but, above all, it’s probably to do with the fact that, after years of dispute surrounding DAT, the groundwork has been laid. Mere days before the release of the first MiniDisc player, the Audio Home Recording Act (AHRA) goes into effect. This law regulates the legality of DAT, but is also applicable to the MiniDisc.

As a result, MiniDisc devices are also required to implement SCMS copy protection. In addition, the AHRA obliges manufacturers to pay licensing fees – both for their devices and media. Despite these negotiated advantages, American record companies are reluctant to release their music on MiniDisc. Sony BMG remains the only major label to actively support prerecorded MiniDiscs.

CD

The MiniDisc’s success is relatively modest and short-lived, as more interesting alternatives emerge not long after its invention. Towards the end of the nineties, CD burners become affordable, and it becomes significantly easier for private individuals to burn audio CDs. The days of the CD as purely a playback medium are numbered.

Source: Raimond Spekking/CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

This presents a problem for the music industry: the copy protection required by the AHRA for digital sound carriers isn’t applicable to the CD. In fact, the law applies only to devices whose main purpose is digital music recording. In the case of a computer with a built-in burner, this clearly isn’t the case. Therefore, SCMS copy protection isn’t mandatory for such devices. This, in turn, means that copy protection can be deactivated very easily. All the software needs to do is change the bit of information that specifies if a sound carrier is copy-protected from 0 to 1.

The industry starts fervently tinkering with new copy protection methods. And fails.

One such method, XCP, causes an especially big uproar. When inserted into a Windows PC, CDs with XCP install software that denies copy software access to the CD – without consent from the user. For this to work, the copy protection software must run permanently in the background. It also hides files and folders with a «$sys$» in their name. With that, the copy protection software operates using the same methods as malware. Technically, the tool is a rootkit – which is why it wasn’t long before XCP was nicknamed «Sony Rootkit». Criminal hackers didn’t have to be asked twice to start abusing XCP as a gateway for malware.

What’s more, the copy protection software itself actually violates copyright, because it contains open-source components without adhering to their licensing terms. But that’s just a side note in the scandal.

There are other copy protection methods with a similar mechanism. YouTuber VWestlife has tested some of them. Long story short, he concludes that not only do they pose a security risk, they’re also useless as copy protection.

Copy protection schemes for CDs prove an imposition for customers. Their existence is accordingly short; only from 2005 to 2007. But one question persists: what has got into the music industry? How could this have happened?

The big picture only comes together against the backdrop of another technical development. Namely, file sharing.

File sharing

If the story had ended at CDs being copied, the music industry probably would have got over it eventually. But – almost simultaneously with the CD burner – two other inventions took hold: MP3 and a strange little thing called the Internet. Together, these factors significantly change the music market.

Stored in MP3 format, music takes up much less space than uncompressed audio. The files are tiny, allowing a huge number of albums to be stored on a hard drive. They’re also small enough that – with a little patience – they can be transferred over the Internet.

In 1999, Napster, a file-sharing software, launches. Napster, which was developed by a teenager, works via a decentralised peer-to-peer network on which all users both upload and download data. It’s the perfect tool for uncontrolled music distribution. Within a short time, the file-sharing platform reaches millions of users, and numerous similar tools spring up.

Music industry representatives are fuming.

In the words of Steve Heckler, Sony Pictures Entertainment: «The industry will take whatever steps it needs to protect itself and protect its revenue streams… It will not lose that revenue stream, no matter what… Sony is going to take aggressive steps to stop this. We will firewall Napster at source – we will block it at your cable company. We will block it at your phone company. We will block it at your ISP. We will firewall it at your PC… These strategies are being aggressively pursued because there is simply too much at stake.»

This offers insight into the ruthlessness of the CD copy protection schemes. The record labels are waging such a bitter war against file sharing that they’re accepting their own customers as collateral damage.

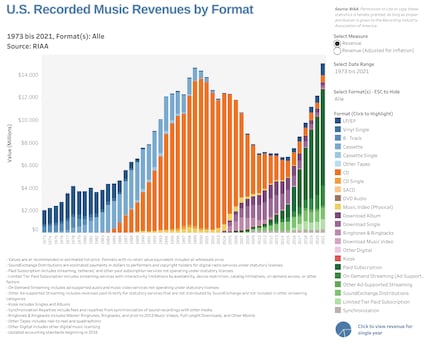

The threat to revenue from file sharing is real. Although CDs are still selling very well in the early 00s, the previously rapid growth is turning into a decline. From 2006 onwards, revenues collapse dramatically.

In 2001, just two years after launch, Napster is forced to cease operations. Other file-sharing networks are also being taken offline. And yet, despite numerous police raids and shutdowns, the industry is losing the battle against file sharing. Decentralised technology makes it impossible to take action against everyone and everything. What’s more, it’s not always clear-cut if the offers truly are illegal.

Online shops

People are downloading music on the Internet. The fact that this saves consumers money – which means lost revenue to the music industry and musicians – is one thing. Plenty of people would be willing to download music online even if it weren’t free; combined with MP3 players, it offers a very practical way to enjoy music.

It takes the music industry years to see digital files not just as a threat, but also an opportunity. The first easy, legal download option comes with the advent of Apple iTunes. In the USA, iTunes launches in 2003; in Germany, in 2004; and, in Switzerland, in 2005. However, iTunes downloads are subject to numerous restrictions. In its early years, all files are DRM-protected and can only be used on a limited number of Macs. Additionally, the iPod operates on a closed file system, meaning the music can’t simply be drag-and-dropped onto a hard drive.

In an open letter (yes, another one), Apple CEO Steve Jobs writes that DRM was necessary to get the four major record labels on board, which together control the distribution of over 70 per cent of all music. Jobs argues for the abolishment of DRM; for one, because it hasn’t yet and may never work to stop music piracy. After all, CDs don’t have DRM – and, in 2007, over 90 per cent of music is still being bought on CDs. It’s also possible to circumvent DRM-restricted content offered by iTunes simply by ripping any CD and importing the songs into iTunes. What’s more, according to Apple, only three per cent of songs on the average iPod stem from iTunes – meaning that only three per cent is DRM-protected anyway. The rest comes from ripped CDs or file-sharing networks.

In fact, the music industry is moving away from the idea of controlling distribution through DRM. That same year, EMI releases its music free of any DRM, and the other major labels follow suit. Paid downloads become more attractive now that files aren’t limited to a specific device. Download sales increase strongly over the next few years; but not enough to compensate for the losses from CD sales.

Streaming

With the advent of streaming services, everything is turned upside down once more. Ironically enough, streaming services are, in fact, copy-protected; I can only listen to a song downloaded from Spotify using a valid Spotify account. But streaming is so convenient that I accept this. If I can play the music anytime and anywhere I want, I don’t care so much about physically owning every single song and being able to manipulate it however I please. And most people probably feel the same.

With that, streaming has put a stop to the seemingly never-ending battle between music listeners and the music industry. Both sides get what they want. The music industry is back to making the big bucks, and listeners can access just about any song whenever they want.

So, is it all sunshine and rainbows? Not quite. While the coffers are ringing – increasingly rapidly, at that – how revenues are distributed leaves much to be desired. Musicians get the short end of the stick. Streaming revenues are a joke, especially for small and medium-sized bands. They can’t possibly live off what they make.

This can’t all be blamed on Spotify and the like, as Spotify doesn’t pay musicians directly. The streaming service pays the music rights holders, i.e. record labels and distributors. These then pass on a portion of the income to the musicians. How much and according to which scheme remains unknown to the public. Rights holders have agreements governing revenue sharing with both Spotify and the musicians. In this video, Spotify explains how the money flows in detail.

After EMI was acquired by Universal, only three major music labels were left. Together, they generate about 70 per cent of revenue. There are fewer major labels than there are major streaming services. Each streaming service has to offer music from all three labels to be competitive. This means that the major labels are in the driver’s seat; they have tremendous power in negotiations. Spotify makes billions in revenue every quarter, but still hardly any profit.

What’s all this got to do with copy protection? That’s simple: from the start, the music industry’s main argument was that it was the guardian of music culture. It likes to portray itself as the patron who makes good music possible in the first place. But the way the streaming business is going shows that the powerful players in the industry don’t care about the subsistence of these creative musicians. The main thing is that they themselves cash in.

Sunshine and rainbows – but only on the surface

From the beginning, the entertainment industry has tried to stop copying by any means possible. For decades, it wasn’t very successful in doing so. This was, in part, due to the schemes themselves: they were easy to circumvent and brought with them everything from disadvantages for buyers right up to malware. But it was also because the music industry had little credibility as an upholder of moral standards. It was easy to see through to the fact that the big players were primarily concerned with filling their own pockets – and less so with saving musical diversity.

Today, everything seems golden at first glance: the music industry has dropped DRM on downloads and CDs. When it comes to streaming, users accept copy protection because it hardly restricts them in their everyday use of media. The war between listeners and the industry is over.

For music creators, however, the situation is catastrophic. Streaming doesn’t provide an adequate livelihood for the vast majority of them. Covid has also sunk concert revenues; and even for performances, lesser-known groups rely on partners, who dictate their terms.

«In DAT you have built a system for rapturous sounds, but you imperil the creators of those sounds.» This was the accusation levied by RIAA President Gortikov against Japanese manufacturers. But, in reality, it holds much more true for the music industry itself.

My interest in IT and writing landed me in tech journalism early on (2000). I want to know how we can use technology without being used. Outside of the office, I’m a keen musician who makes up for lacking talent with excessive enthusiasm.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all