Background information

The strange freedom of parenting older children

by Michael Restin

When toys start to get boring and grown-up stuff isn’t yet an option, parents and children are faced with a whole new question. What to do when there’s nothing on the wish list?

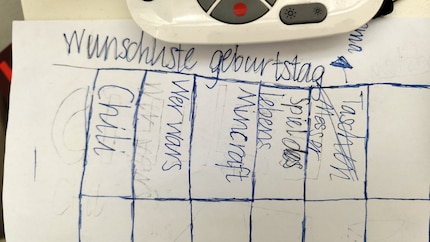

There’s a phrase my children say that makes me increasingly nervous before birthdays: «I don’t know what I want.» I used to rely on getting a reasonably realistic list of major and minor wishes. I was able to distribute them among the inquiring relatives and the children’s birthday party attendees. A bit of Lego Ninjago here, a puzzle there, a Tiptoi book to boot and everyone was happy.

And now they don’t want anything. From birthday to birthday, they find it increasingly difficult to come up with their own ideas.

In a way, it’s great that my children are perfectly happy with what they have. And to be honest, like most people, we have more than enough stuff in our playroom that’s no longer used and, with a bit of luck, will be sold at the next school flea market. Nothing new isn’t bad, I could easily get on board with that. But it’s not that simple.

Because although they might not be asking for anything, they’re expression isn’t all that happy. Rather perplexed and slightly worried. The excitement of a few presents and a cake on the table on the day doesn’t just disappear when they haven’t wished for anything. And for me and other parents, the pressure increases to come up with something. It’s not just my children who are making fewer specific requests. It seems to be a common thing at this age.

When the candles on the cake slowly reach double digits, the gift ideas dry up. Gone are the days when the wish lists were so ambitiously filled that you couldn’t fulfil every single one. In think it’s important to realise that you can wish for a lot, but you can’t have everything. If expectations are kept in check and the joy outweighs the disappointment, gift-giving can be fun for everyone involved.

At least it was for me – when I knew what to look for. Nowadays, even the largest range of products is of little help to me. Quite the opposite, in fact, it’s frustrating. I no longer have to click through the toy category. The bestsellers you find there have long since been in one of our cupboards and are now gathering dust, have been given away or were sold. Nothing is as old as last year’s gift idea when the children are growing up.

Yet, I feel like they’d actually be happier to see gift-wrapped boxes on the table than having vouchers for excursions or other activities that they can only enjoy on day X. According to this article, this seems to be the case until around the age of twelve.

Toddlers derive feelings of happiness from tangible things. They don’t have the treasure trove of memories and anticipation is a foreign word to them. It’s all about the here and now. Toddlers are just excited by the fact they can tear up the wrapping paper.

Then the wishes become more specific. The kids are fuelled by hobbies and what theysee in their peers. And at some point they become quite rational. Along the lines of: «everyone please put your money together, I need a new smartphone or I’ll buy something with the money if I need it». Right now, though, we’re in a transition phase.

Parents need to come up with ideas and question their own motivation for gift-giving so that presents are more than just shiny coins for their piggy bank. Are we ticking off another to-do? Or are we actually giving it some thought?

«We’re trying to give parents their own competence back by raising their awareness of why they’re giving something to their children,» says neurobiologist and author Gerald Hüther in an interview with Der Spiegel (article in German). Actually, that’s a good question. Why do we give presents?

Of course, first and foremost we give gifts to bring joy. But in the back of your mind, there’s always the worry that you’ll be met with disappointment. So with every birthday there are more and more presents, even though the children are overwhelmed by the abundance (articles in German).

And there are consequences of thoughtless gift-giving. Those who are showered with stuff instead of attention play less deeply and creatively, don’t develop healthy self-esteem and tend to seek their happiness in consumption even in adulthood.

In a lot of ways we make our lives easier. Then it doesn’t matter as much if we make a mistake. But conscious gift-giving also means taking a little risk and surprising people. «If it’s approached with love and responsibility, it makes it easy for parents to think of meaningful gifts,» says neurobiologist Hüther.

It’s about recognising needs that the child may not have recognised themselves. And spending time together. In the best case scenario, this can lead to a new hobby or even a deeper relationship. My colleague Philipp Rüegg perfectly demonstrated this recently.

Recognising their needs, when they’re not so obvious, is easier to write in a book than put into practice. And when desires slowly migrate to the digital world, I first have to explain that love and responsibility mean there’ll certainly be no iPhone or more gaming time.

I don’t have a real solution to my «problem». I’ve just learnt that gifts should be something unifying. And to connect with each other because they go hand in hand. In Philipp’s case, the telescope increases its value through shared evenings. A new bike is nice, going on a trip together is nicer. You need at least two to play table tennis. The relationship is the most important piece that holds everything together and turns a gift into an experience.

Have you had similar experiences with your children and how did you deal with them? Are you happy the wishes have stopped, have you reduced the number of gifts or tried something new together? I’d love to hear your views and ideas in the comments section.

Simple writer and dad of two who likes to be on the move, wading through everyday family life. Juggling several balls, I'll occasionally drop one. It could be a ball, or a remark. Or both.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Martin Jungfer

Background information

by Michael Restin

Background information

by Martin Rupf