Guide

Myth or fact: does vitamin C have an effect on colds?

by Anna Sandner

Flawless skin, sparkling eyes – and a supplement for everything. On Instagram, dietary supplements are presented as miracle cures, while any risks and a lack of regulation are barely mentioned. Foodwatch shows how dangerous advertising claims can be.

When you’re scrolling through Insta, between workout reels, self-care tips and avocado on toast, someone suddenly pops up who looks like they’ve come straight out of a lab: perfect skin, wide-awake eyes, obviously super healthy – and all of this is supposedly thanks to «this one supplement».

Sound familiar? Then you might have already noticed that a surprising number of medfluencers claim to have found that one miracle cure. That one remedy we all lack to become healthy, happy, fit, slim or whatever it may be, without any further effort. Sometimes it’s a green nutrient drink, sometimes a vitamin supplement, sometimes a gut flora miracle capsule. Sound too good to be true? It is.

Consumer protection organisation Foodwatch thought so too, so it took a closer look at the phenomenon of Instagram miracle healers and super doctors. The results of its report (in German) are as clear as they are alarming. In its view, every single Instagram story they examined containing an ad with health claims was illegal. So why are they still being shared? More on that later.

More than half of Germans take dietary supplements at least once a year. In 2023, these products generated sales of over three billion euros in pharmacies alone. But Instagram’s the shop window now: brands such as ESN, More Nutrition and Sunday Natural are specifically targeting influencers to market their products as essential for health and wellness.

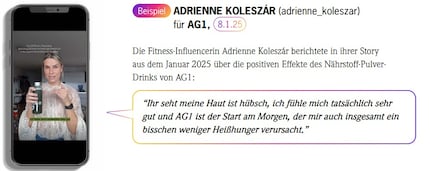

Foodwatch monitored 95 German-language health and fitness accounts for 20 days. It found a total of 674 stories advertising supplements – all of which were illegal, it says. This isn’t an isolated incident; it’s systematic.

Dietary supplements are unnecessary for most people and can even be harmful in high doses.

The rules are actually easy to understand: the EU Health Claims Regulation only permits scientifically proven health claims. Everything else – especially disease-related claims such as «cures joint pain» – is prohibited. In Switzerland, too, only scientifically proven health claims can be made about food products.

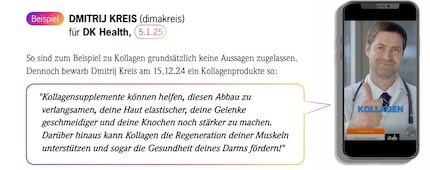

The reality on Instagram, however, looks a bit different. Self-proclaimed health professionals merrily promote substances with no approved health claims. Collagen is one of them. According to Dmitrij Kreis: «Collagen supplements make your skin more elastic, your joints more supple, your bones stronger…» Sounds great, but unfortunately, there’s no scientific evidence for it, so his claims aren’t allowed.

Why do these advertising messages seem so convincing? Because influencers present themselves as your best buddies, share their personal success stories (whether true or not remains to be seen), and – to top it off – offer you exclusive discount codes. All of this means that these «sales videos» aren’t immediately recognisable as traditional advertising. Plus, almost one in five stories isn’t officially labelled as advertising – the line between honest recommendations and hard-hitting sales tactics becomes blurred.

Dietary supplements are food, not medication. They’re also no substitute for a healthy diet. They’re barely regulated, require no proof of efficacy and they often contain too high a dose or don’t contain the active ingredients they claim to. Most people don’t need them – and they can sometimes even be harmful. Here are Instagram health swindlers’ bestsellers – and what’s really behind them:

Protein: a balanced diet is usually enough, even for athletes. Targeted intake can only be beneficial for very intense training. In such cases, however, a doctor or nutritionist should be consulted.

Vitamin C: contrary to persistent advertising claims, it doesn’t ward off colds. Besides, you can easily get what you need through fruit and vegetables.

Magnesium: here, too, there’s a widespread misconception that’s often used as a sales pitch: it doesn’t help with muscle cramps. It’s only useful if you have a proven deficiency.

Vitamin D: many people in this part of the world do lack it, and it can be beneficial in winter. But even then, only after consulting a doctor.

Multivitamins: there are no proven health benefits for these either – but there is a risk of overdose.

Many supplements aren’t only unnecessary; they can be harmful too. There are no legally established maximum amounts for vitamins and minerals. Manufacturers can therefore adjust dosages as they please – and they do. Foodwatch found that over half of the products exceed the recommendations of the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. Seven per cent even exceed the maximum values set by the European Food Safety Authority.

Another trick is that, by law, the actual number of ingredients can be up to 50 per cent higher than the amount stated on the packaging. By half! So, you never really know exactly how much you’re actually taking. In short, dietary supplements aren’t a harmless lifestyle product. At worst, taking them carelessly puts your money and your health at risk.

If it’s strictly forbidden, why’s it so easy for pseudo-experts to keep advertising on Instagram? Because the authorities are hopelessly overwhelmed. They can barely manage the required checks in supermarkets – comprehensive social media monitoring’s hopelessly unrealistic.

The result is that the internet – especially social media – is virtually lawless. Companies and the influencers they work with can often promise people the moon without verifying the accuracy of information.

Consumer protection agencies regularly warn against misleading advertising and the risks of dietary supplements. They and other consumer associations such as Foodwatch can issue warnings and lawsuits, but this takes time, costs money and by the time that’s all done, the products are long gone.

So, their advice is to stay sceptical and question claims – especially when they sound too good to be true and come with a discount code.

Science editor and biologist. I love animals and am fascinated by plants, their abilities and everything you can do with them. That's why my favourite place is always the outdoors - somewhere in nature, preferably in my wild garden.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Siri Schubert

Background information

by Michael Restin

Background information

by Debora Pape