News + Trends

Girls overtake boys in pocket money - but have none of it

by Anne Fischer

The gender of a child shouldn’t play a role when it comes to pocket money. Yet, many surveys suggest there are disparities. Is this really true? Here’s what the statistics and the media have to say.

Many children receive their first pocket money around the time they start school. Whether they do and how much this is depends on various factors. From parenting style to financial means to comparisons with peers. Gender too, or so it seems. However, how the subject is reported on is a subject in its own right.

After all, the headline «Pocket money gender pay gap» has been making international headlines for decades. You can find them in England (boys get 20 per cent more), in Austria (20 per cent more), in France (almost 14 per cent more), in New Zealand (13 per cent more). And the list goes on and on. Similar figures were circulating in Germany – until news broke in 2023 that girls were actually getting more in the meantime.

Is this the turning point? Are Germany and Switzerland pioneers when it comes to equal rights? Here in Switzerland, the pocket money study conducted by Sotomo and published by Credit Suisse in 2017 already explicitly stated that girls don’t receive less (study in German).

Often banks, insurance companies or publishers are behind these surveys. And they don’t just want a representative survey, but also a story that will attract as much attention as possible. Everything equal and hunky-dory? That won’t make the headlines. So every statistically significant difference (whether it’s practically relevant or not) is exploited and full focus is placed on seemingly explosive findings. And these are served up in the form of a press release.

What’s important on this topic is what’s not reported on, wrote German newspaper «Der Spiegel» back in 2016. In the article, a statistics professor and a stochastics professor show how questionable survey results become better known than serious ones. When a good headline is delivered along with the survey, media outlets essentially become banks.

Of course, just because some headlines aren’t true doesn’t prove that children’s financial matters are totally fair. A study published in 2024 by St. Andrews University, for example, doesn’t refer to surveys. Instead it relies on hard banking data from a British app parents use to pay their children’s pocket money and other allowances.

The accounts of over one million children show that up to the age of ten, girls receive around ten per cent less than boys. They also receive smaller sums as gifts of money and are paid less for household chores, which can also be rewarded via the app. All this despite the fact that almost three quarters of transfers come from mothers.

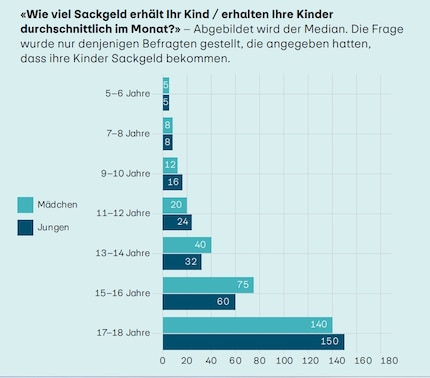

There’s also some evidence revealed in Swiss pocket money studies that boys are somewhat better off, especially in the first years of school. According to a current study from May 2025, children of school age initially start with the same amount according to the old formula of «one franc per week and school year». At the age of five or six, they receive five francs per month and at the age of eight they receive an average of eight francs.

But then the gap widens. According to the results of the representative survey, for which 1,429 parents in German-speaking and French-speaking Switzerland were questioned, boys receive an average of four francs more per month as they progress through primary school. Parents also have more lengthy conversations about money and finances with boys.

Unfortunately, it’s still unclear who is raising the topic. But the previous study from 2017 suggests that even primary school pupils are more demanding. Younger brothers in particular seem to cash in early, while younger sisters have to wait longer. «One reason could be that younger brothers insist on pocket money as soon as an older sibling receives it, whereas girls are more willing to wait until they’re the same age,» the study suggests.

So it’s surprising that the trend then reverses – which can be seen in both the British financial data study and the Swiss survey data. This means that girls not only catch up, but also receive a little more pocket money later on and and do so for longer. One explanation for this in Switzerland is that more girls attend grammar school than boys, which requires longer financial support. A more general explanation is that consumer behaviour of boys and girls changes with age.

According to the study, boys in their first years of receiving pocket money are after more expensive toys, while girls in their (pre-)teenage years put more expensive products in their shopping baskets. According to the financial data study, they start spending more money than boys of the same age from around the age of eleven.

Perhaps they’re also smarter in getting money out of their parents. The fact the amount of money seems to be based on the child’s wishes and needs suggest that the adults aren’t being consistent in their teaching. And this, despite the fact that parents in the latest pocket money study, expressed that their greatest concern is their child might spend too much money on unnecessary things.

Finally, it comes down to what feels right. It’s hard to believe that girls are deliberately disadvantaged when it comes to pocket money. What I definitely believe, though, is that parents are easily influenced and tend to trust that everything will somehow balance out over time. Why? Because being fair is much easier said than done, which results in discrepancies like those described above.

Surveys are often easy to pit against each other. «Parents from German-speaking Switzerland grant their children higher amounts than those from French-speaking Switzerland,» according to the latest pocket money study. «On average, children in French-speaking Switzerland receive four francs more», announced Generali in December 2024. So it always depends who you ask. And how you ask. Children are aware of this too, which is probably why they’re always trying to talk their parents into giving them a few extra francs.

Simple writer and dad of two who likes to be on the move, wading through everyday family life. Juggling several balls, I'll occasionally drop one. It could be a ball, or a remark. Or both.

Interesting facts about products, behind-the-scenes looks at manufacturers and deep-dives on interesting people.

Show all

Background information

by Michael Restin

Background information

by Debora Pape

Background information

by Michael Restin